The Time Snatchers

The Time Snatchers

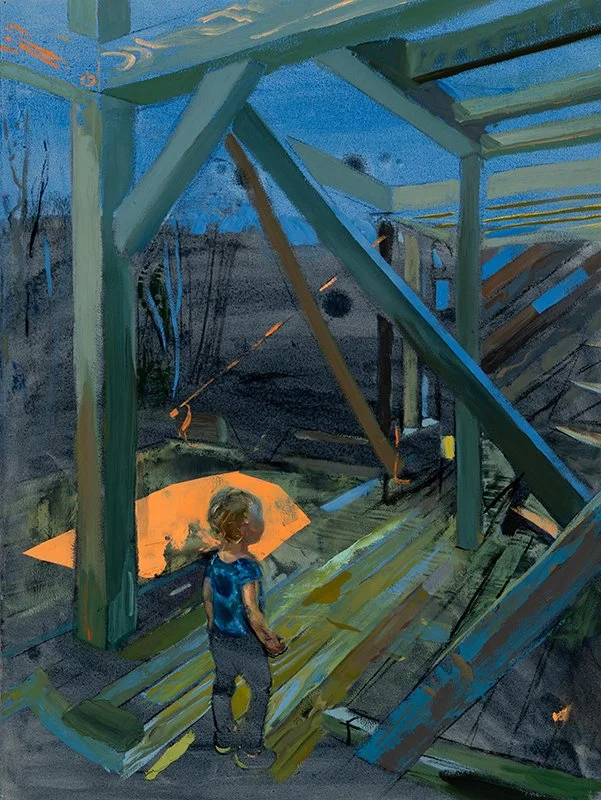

Beneath the rough outline of an entryway, a child surveys the strange space surrounding her. Washes of blue paint in the background and sky convey the stillness of the evening hours or early morning. The architecture is unresolved. The trees are loose wisps in the background. Likewise, the painting seems to have unfolded quickly, confidently.

In Sister Studio, Suzanne Schireson imagines constructing a studio space for her young daughter. For Schierson, the studio connotes any space where any type of creative act can take place. Having a creative outlet is—for Schireson and many others—an important way she cares for herself. In her painting, she fixates less on the specific dimensions or appearance of the building, highlighting instead the necessity of its existence. Creating the painting underscores the need for such a place to exist for her daughter, maybe for all daughters.

Suzanne Schireson, Sister Studio (2021); Oil on paper, 30 x 22 inches.

Sister Studio belongs to a series that began shortly after the birth of Schireson’s second child. Her daughter’s early years dovetailed with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. As Schireson was beginning to resume her painting practice in earnest, she found that she was unable to return to her studio. Priorities shifted, businesses closed, and schools went remote. With new demands on Schireson’s time, she traded large-scale canvases for quicker paintings on paper, and she resumed working in a makeshift studio in the unfinished basement of her home.

Throughout this body of work, Schireson focuses on the spaces where creative acts of self-care occur. She began by collecting stories from her friends and colleagues—from other mothers. She asked about the ways they continued to fulfill their own needs after becoming a parent. As a mother and an artist, Schireson needed to adopt new strategies for balancing both roles.

Caring for another, particularly the vulnerable—the infirmed, elderly, or newborn—expands to occupy any empty space. This type of care reorders time. Time is lost and simultaneously never-ending. With less free time on hand, Schireson re-evaluated what she wanted to communicate through her work. Schireson learned that her conception of the studio no longer existed as a fixed space. She began to conceive of her creative practice as a radical form of sustenance—necessary and untied to any specific environment.

This sustenance can take many shapes. Some of Schireson’s recent paintings illustrate physical spaces, while others are imaginative. A welder fabricates a metal shop in her garage. A writer sits before an open laptop at her desk. A textile artist bleaches fabric in her front yard. Some are outdoors, and many are modest in scale. Most seem to occur at night or at other odd hours. The creative acts in Schireson’s paintings are as varied as the spaces the characters inhabit.

Suzanne Schireson, Purple Room, Turquoise Moon (2022); Oil on paper, 30 x 22 inches.

Sometimes the figure is removed from the composition altogether. When the figure disappears, the viewer takes the perspective of the person using that space. What remains is charged, electrified by Schireson’s saturated color palette. Neon pink, magenta, and vibrant tangerine hues bring a conceptual heat to her paintings. Absent a person, these environments await activation.

Schireson’s places serve different purposes, but the paintings all explore the need for nourishment. Together, they ask the question: how do the caretakers take care of themselves? Over the past two years, in particular, Schireson discovered that the answers varied dramatically, Still, the act of refueling—however harried at times—trumped the significance of the actual space. As artist Ruth Asawa, a mother of six, once advised in an interview, “Learn how to use your snatches of time when they are given to you” [1]. A studio can be a kitchen table, a scrap of paper, or fifteen unfettered minutes.

Installation view of Night Studios, Seton Gallery, University of New Haven, February 2022. Photographer: Liz Calvi.

Some artists learn to maximize these snatches of time, while others strive to carve out long stretches, frequently at the expense of others. The title of Schireson’s exhibition nods to a memoir written by the daughter of Philip Guston, an artist in the latter category. In Night Studio, Musa Mayer recalls the ways that Guston created space for his work, trading time alone in the studio for the time they could have spent together.

The book opens in the months following Guston’s death. Mayer describes his unused studio with the clinical character of a morgue: “Paintings rest in air-conditioned berths in the storage room next door, the drawings in the long drawers of two steel cabinets… black ink has dried in its bottles” [2]. She mourns how unfulfilled she felt by their relationship, and she offers glimpses of Guston in the studio as the stereotype of the lone artist.

Guston blocked out others to fuel a solitary passion. Mayer spends a portion of the book tracking down her mother’s murals in a rural post office and a forest service building, both painted before her birth. She reflects on the fact that both she and her mom (Musa McKim) stopped painting when they became mothers—a stark contrast to Guston’s rigid commitment to her practice.

Like Guston, the characters of Schireson’s paintings appear mostly alone, but they are not relaxed. Some seem frazzled. Many are multi-tasking. They have not escaped. Rather, they understand the preciousness of their time with newfound clarity. Schireson asserts the possibility that becoming a parent—or at the least, balancing competing responsibilities—can spark creativity with more urgency and depth. The necessary pauses of parenting make room for Schireson to contemplate her practice, prompting growth. One by one, Schireson is building her sister studios, her structures breathing inspiration into barren spaces.

Installation view of Night Studios, Seton Gallery, University of New Haven, February 2022. Photographer: Liz Calvi.

[1] “Celebrating Ruth Asawa,” Google. May 1, 2019, https://www.google.com/doodles/celebrating-ruth-asawa

[2] Musa Mayer, Night Studio: A memoir of Philip Gustin (New York: Knopf, 1988) 241-2.

The essay above was included in the catalog of Suzanne Schireson’s solo exhibition Night Studios, on view at Seton Gallery through March 3.

Suzanne Schireson

Suzanne Schireson is an artist based in Providence, Rhode Island. She is the recipient of a Rhode Island State Council on the Arts Fellowship and two Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grants. Her work has been featured in Hyperallergic, The Providence Phoenix, and The Boston Globe. Recent solo exhibits include Inside Room, Tiger Strikes Asteroid GVL; Mother Hermit, West Virginia Wesleyan College; and Ears May Talk Behind Your Back, Smith College. Her work has been exhibited at The Woodmere Art Museum (Philadelphia, PA), the New Bedford Museum of Art (New Bedford, MA), the Sori Art Center (Jeollabuk-do, South Korea), the Srimanta Sankaradeva Kalakshetra (Guwahati, Assam, India), and The Carrousel du Louvre (Paris, France). Suzanne attended Indiana University (MFA. 2008), the University of Pennsylvania (BFA. 2004), and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (Certificate 2003). Schireson is an Associate Professor of Art and Design at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

Follow her on Instagram: @suzanneschireson