The Million-Petaled Flower of Being Here | Joseph Saccio

The Million-Petaled Flower of Being Here | Joseph Saccio

Joseph Saccio in his Erector Square Studio, August 2019. Photo: J. Gleisner.

Joseph Saccio leads me down a narrow staircase to the damp basement of building six inside Erector Square. At 84 years old, Saccio walks carefully, using a metal flashlight to illuminate the rooms. Fragments of his large sculptures begin to emerge from the darkness. Against one wall, he shows me the shiny amber surface of a gnarled root ball. This wooden base came from a felled tree that he had retrieved, incorporating the natural structure into one of his carved sculptures. For over thirty years, Saccio’s studio has been located at Erector Square, where his sculptures have been accumulating, now tracing his trajectory as an artist.

Trees are a recurring theme within Saccio’s pieces, many of which explore the slow and inevitable decomposition of these organic bodies. The impetus for this emphasis on decay comes from a personal tragedy: Saccio’s 12-year-old son Milos was fatally struck by a bus crossing the street on Whitney Avenue in 1979. Reeling from this loss, Saccio rented his first studio inside an old factory along the Quinnipiac River, explaining, “The death of my son strengthened the need to express loss and redemption through making art.” Many of his early sculptures were memorials to Milos which incorporated scraps of his clothing. He planted a weeping beech tree at Foote School in his son’s memory, too.

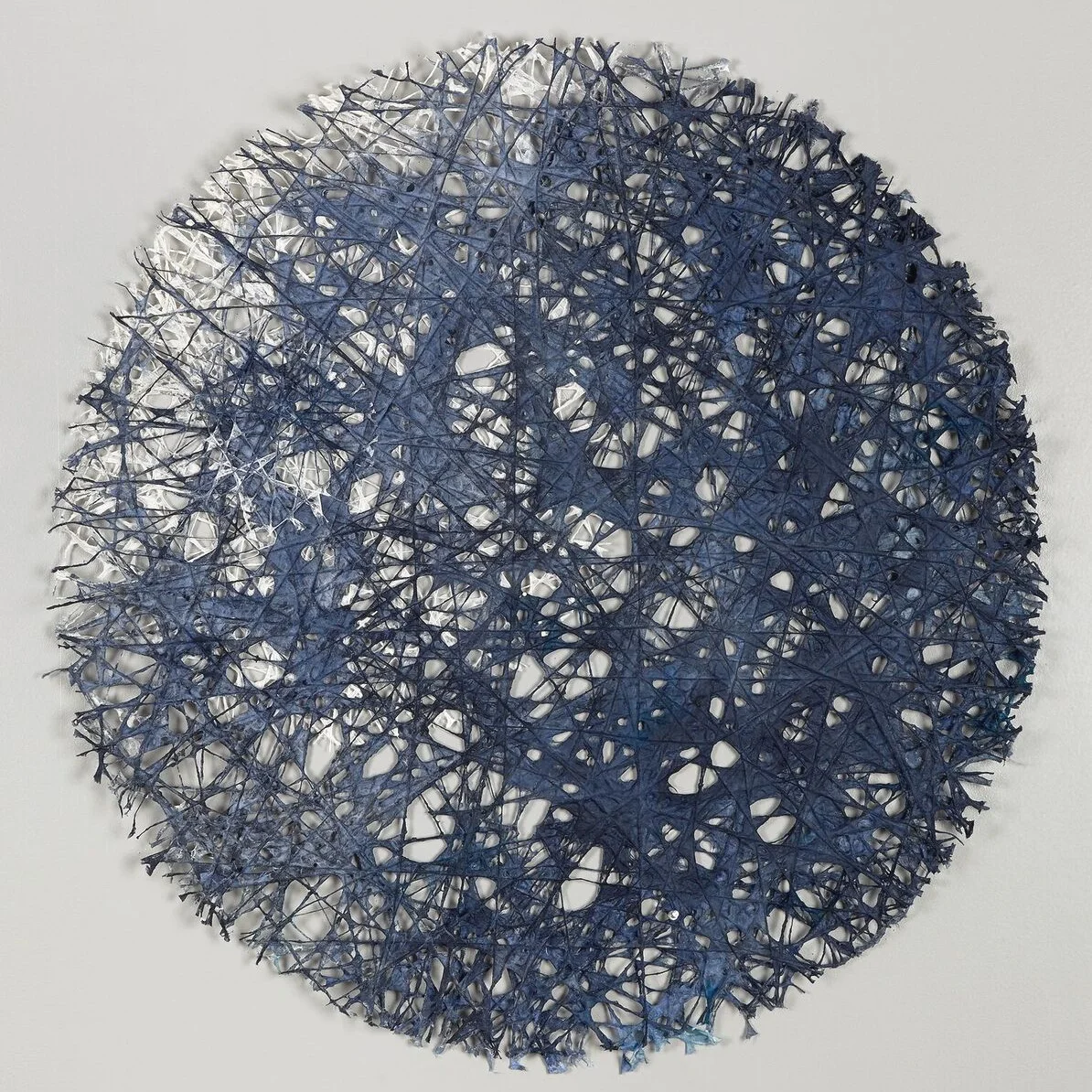

Joseph Saccio, Memory Trap. Image courtesy of the artist.

During the weekdays, Saccio worked as a child psychiatrist, but all his free time was spent inside his studio. Growing up in Manhattan, he had won art competitions during high school for his paintings and drawings. His parents were uneducated immigrants from Sicily, and while his family wasn’t destitute, it had been challenging, Saccio recalled. He wanted to choose a path that would offer him greater financial security than a career in the arts. At that time, Saccio had been a devout Catholic. Desiring to help others, he went to medical school and planned to continue to pursue his art on the side.

“I had the imagination and interest to pursue child psychiatry because it was a lot like making art,” Saccio said. He specialized in early childhood development, working with children to overcome a range of problems. This work often entailed allowing children to create their own fantasy worlds, where they could practice resolving issues from their real lives together. He remembered one patient who had been selectively mute—she only spoke to members within her immediate family. Saccio and this patient made elaborate drawings during her appointments, and little by little, she started talking to other people. She never spoke directly to Saccio, but he understood that they had their own nonverbal way of communicating with each other.

Joseph Saccio. Henge Installation of the three versions of Memory and Metamorphosis

floor view 1. Loomis Chaffee School, Windsor, CT. (2013). Image courtesy of the artist.

Slowly, Saccio began creating more space within his schedule for art. His private practice allowed him to taper his appointments, retiring gradually at the age of 70. The rigor of his work within the medical field carried over as he transitioned into a full-time sculptor. “As a practitioner in child psychiatry, I would see my first patient at 8:00 a.m., so I also came to the studio every morning at 8:00 a.m.,” Saccio explained. He joined Kehler Liddell Gallery and began participating in City-Wide Open Studio events as a way to become more involved with the New Haven arts scene. With time, he was invited to show his work around town and with other artists who admired his sculptures.

This November, work from over thirty years of Saccio’s career will be exhibited in a retrospective titled IN A DARK WOOD, WANDERING at the Housatonic Museum of Art. His first museum show follows his 85th birthday. “It’s probably my swan song,” stated Saccio. In the past few years, his arthritis has worsened and he has been losing muscle strength in his legs in particular. It is unclear how much longer he will be able to continue making his sculptures, which are often very large and extremely heavy.

Looking back on his career, Saccio said, “It seems to have been a very straight line.” After the death of his son, his need for an outlet to process his grief propelled his studio practice. “I wanted people to see that things can be transformed,” added Saccio, “and that there’s always a response of life from death.”

All of Saccio’s quotes are from a conversation with the author at Saccio’s studio in Fair Haven, Connecticut on August 7, 2019. In a Dark Wood, Wandering opens November 7 at the Housatonic Museum of Art in Bridgeport. Read more about this commissioned project here.